How to resolve the complexities of crop rotation

Robin Gale-Baker, from Sustainable Macleod, discusses the complexities of crop rotation. This is one of a series of articles she has written about growing techniques (see right hand sidebar). She has also written a number of articles about growing various vegetables, herbs and fruit trees.

For an introduction to the concept of crop rotation, read this page. Note that the crop rotation on that page is a bit different than Robin’s in order to avoid two heavy feeders (cucurbits and solanums) following each other.

Whenever I plan my next season veggie garden I’m faced with the tricky question of how to rotate my crops. It may sound simple – just grow something different in each plot each season – but in reality there are a lot of factors to take into account which do not resolve easily.

Crop rotation is a system of planting a different crop in a different bed each year, in an ordered sequence that best utilises the soil inputs and outputs of each vegetable family for the health of all.

The purposes of crop rotation include:

- To maintain healthy soil structure by increasing biomass in the soil. Biomass consists of roots, spent plant material and dug-in green manure crops – that is, organic matter.

- To increase the nutrient levels in the soil (particularly nitrogen) and appropriately feed each crop.

- To help prevent soil-borne diseases such as root-knot nematode.

- To help control insects and weeds and prevent specific weeds and pests associated with specific crops taking a hold.

- To increase biodiversity, attract beneficial insects and increase micro-organisms in the soil.

- To sequester carbon in the soil.

- To avoid having to use chemicals and non-organic fertilisers.

In other words, crop rotation is about achieving resilience!

In designing the next season’s rotation, the following can be problematic:

- Previous season’s crops are not yet finished in a bed you need to plant for the following season.

- Plants from the one family may have summer and winter varieties that cannot be planted in the same bed (for example, the Solanaceae family has summer croppers such as tomato, capsicum, eggplant and winter croppers such as potato).

- Space and number of beds available.

- Plants that, for space or timing reasons, don’t easily fit into usual rotations (for example, sweetcorn, potatoes and pumpkin).

- The need to leave a bed or beds fallow sometimes (though there is now some evidence that this is detrimental to soil health and that it is better to plant a green manure crop – a combination of legumes and grasses).

- The sunlight requirements of crops (for example, capsicums prefer the hottest part of the garden, eggplants the second hottest, leafy greens more shaded areas).

- Bad companions which should ideally not be planted together eg parsnip and carrot, pumpkin and potato.

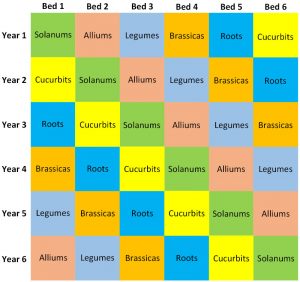

A crop rotation system can have any number of beds but the ideal is a 6 bed system. Knowing the family names of crops is very useful, if not essential, as these form the basis of rotation. Here’s the 6 bed system that I adopted from Peter Cundall decades ago.

A crop rotation system can have any number of beds but the ideal is a 6 bed system. Knowing the family names of crops is very useful, if not essential, as these form the basis of rotation. Here’s the 6 bed system that I adopted from Peter Cundall decades ago.

- Bed 1: tomato, capsicum, chilli and eggplant (Solanaceae or solanums). These love acidic soil.

- Bed 2: onion family (Alliaceae or alliums). As these follow tomato family, add lime or dolomite to the soil a month before planting.

- Bed 3: peas and beans (Leguminosae or legumes). These add nitrogen to the soil.

- Bed 4: cabbage family (Brassicaceae or brassicas). These need a lot of nitrogen.

- Bed 5: root crops such as beetroot and carrots plus spinach, chard, celery and some herbs.

- Bed 6: pumpkin family (Cucurbitaceae or cucurbits) including cucumber and zucchini plus sweetcorn.

Each crop only grows in the same bed every 6 years.

Growing a green manure crop especially after a legume crop is good practice. You may find you have a spare bed after summer cropping for this, one that might otherwise lay fallow till spring.

Rotating crops avoids the pitfalls of monoculture which we see in large scale commercial farming including development of competitive weeds, pests, loss of nutrients and biomass, and subsequent potential wind and water erosion.

Crop rotation in the home garden requires us to be thinkers and planners. We need to know that grasses produce high biomass and legumes low biomass; that legumes add nitrogen to the soil and cabbage family chew it up; that pH must be adjusted sometimes with high (alkaline) pH, for example, causing potato scab and being unsuitable for the tomato family; that hours of sunlight must be planned for (full sun/partial sun/ partial shade); and that, best of all, we can grow organically with confidence.

Thanks for this concise info, Robin.

Trouble comes when you want two beds of tomatoes, because the family eats more of them than any other veg!!

Do you think crop rotation matters as much if you top up raised beds each season with new veg potting mix, own compost and mulch?

Also does this matter as much with guild beds?

Hi Jay,

Re topped up beds: clearly it matters less but, in principle, it still matters.

Re guild beds: there can conflicts between different approaches and you just have to decide what is most important for you. For example, I used to do companion planting but it doesn’t really fit with crop rotation because the two together are too restrictive.

Thanks Guy!

Is this rotation map right? I don’t understand why cucurbits (heavy feeders) would follow solanums (also heavy feeders).

Hi Natalie and thanks for your comment.

I actually agree with you which is why the ‘official rotation map’ on this website (https://localfoodconnect.org.au/community-gardening/crop-rotation/) is a bit different.

I’ve also added some words at the top of the article (in the red box) on the subject.

Guy

Very helpful, Robin, thank you.